Between now and election day, I’m going to be publishing swing state guides roughly once a week. They’ll cover the seven states that currently look likely to decide the election - North Carolina, Georgia, Arizona, Nevada, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania - plus Nebraska’s second congressional district. The posts are designed to be digestible guides to understanding the political geography and demographics of each swing state, allowing you to be a more savvy consumer of news in the run up to election night - and on election night itself.

And it’s really not just about election night. This week’s guide is about North Carolina - a state which starts mailing out mail-in ballots this week. Yep, that’s right - voting in the 2024 election is already beginning. These guides are designed to help you make sense of it.

My guides are designed to be different to ones that you will find elsewhere. I’ve never had a lot of respect for the “statistical nerd” approach to understanding U.S. elections. Every election cycle, the media is full of commentators who can tell you how many Electoral College votes each state has but know nothing about the political geography of Atlanta or the history of western Pennsylvania. I’m not trying to fill you full of numbers - although of course some data is always necessary - but rather to put together an informed narrative that helps you understand what is really happening under the hood in each state.

This first swing state guide is available to all subscribers, but many future ones will not be. Upgrade to paid in order to be able to read all of the guides and to support me in producing this content.

North Carolina is part of the Sunbelt, the fast-growing part of the United States that stretches from Florida in the east to California in the west. The other key swing states in the Sunbelt are Georgia, Arizona and Nevada. When Biden was still in the race, he was really struggling in these states, meaning that pretty much his only path to an Electoral College victory lay through the Midwestern swing states of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Now Harris is the candidate, she is leading or drawing even in all of the Sunbelt states too, with the latest polls showing her just 0.2% behind in North Carolina. This gives her potentially two paths to an Electoral College victory - one through the Midwest, and one through the Sunbelt. And within the Sunbelt, North Carolina is particularly important - according to Nate Silver’s forecasting model, Trump has just a 3% chance of winning the Electoral College if he loses North Carolina.

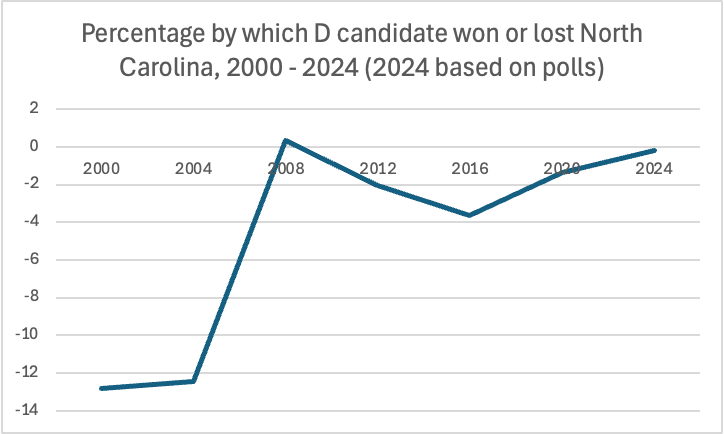

Much like Georgia, North Carolina is a fairly recent addition to the roster of swing states. Long reliably Republican, it surprisingly voted for Barack Obama during his 2008 landslide. Although Republicans have never returned to their pre-Obama performance in the state, Democratic candidates haven’t managed to repeat Obama’s feat either. Biden came the closest of any, losing by just 1.3% in 2020 - making North Carolina the state in which Trump’s margin of victory was the smallest. That means that an epochal shift is not required for Harris to win the state this year, but that she’s still fighting uphill.

So what would it take for Harris to win? To understand that, you need to dive into North Carolina’s political geography.

Urban, rural, and a different type of rural

One of the most notable features of contemporary American politics is the urban/rural divide. Look at maps of how the country or particular states voted and you see blue dots in a sea of red. Conservatives sometimes like to claim that this shows that the country is really “red”, but that’s ludicrous - it’s just that many, many more people live in those blue dots, which are the country’s urban centers. Urban residents tend to be more educated, younger, and more liberal - all characteristics that are more likely to make them vote Democratic.

But the urban/rural divide is also simplistic. Suburbs, for instance, are where a lot of swing voters live, and can shift allegiance over the course of election cycles. Rural areas are also not necessarily always deep red - and this is particularly the case in North Carolina.

If you want to understand the political geography of North Carolina, it’s useful to think about three types of region:

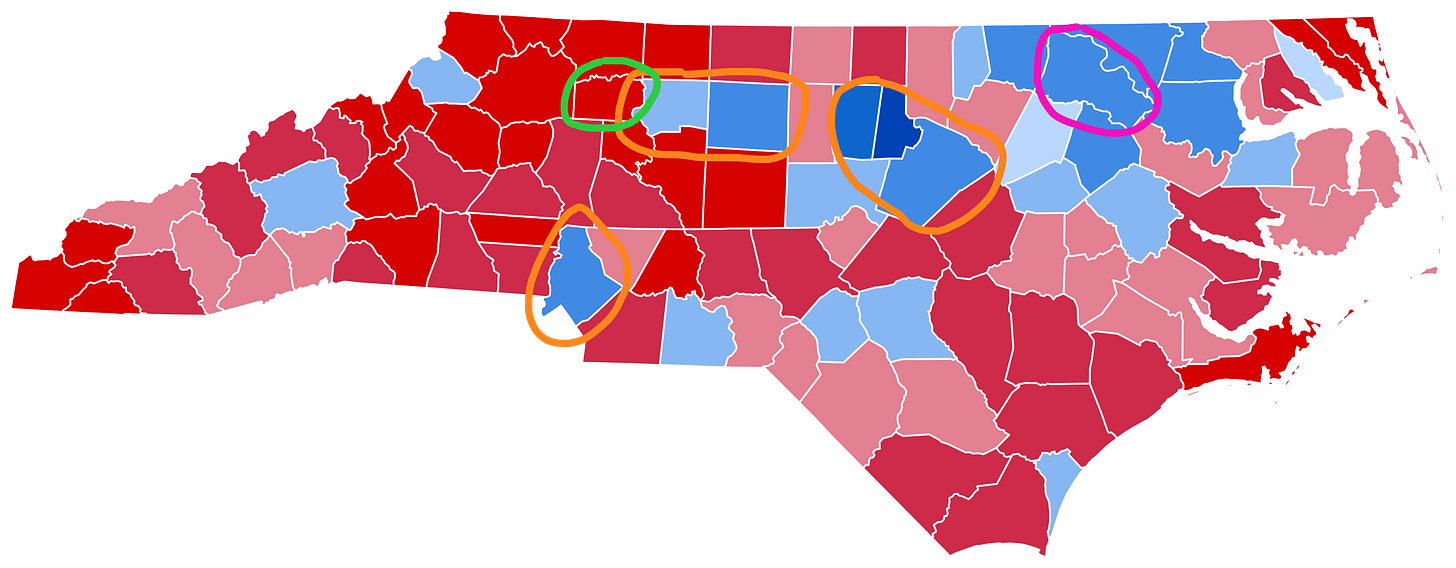

Deep-blue urban areas. The first type of region are the urban centers. On the map above, these are circled in orange. In the southwest of the state you have Charlotte, in Mecklenburg County; in the center-west Greensboro and Winston-Salem, in Guilford and Forsyth counties; and in the center-east the Raleigh-Durham-Cary metropolitan area, stretched over Wake, Durham and Johnston counties and spilling into many others nearby. Democrats run up margins of something like 25 - 70% in these counties. But it’s worth noting that because they’re so populous, that’s still a lot of votes for Republicans here too.

Deep-red rural areas. Many of the reddest areas on the map are relatively sparsely populated rural areas which have a history of voting Republican by huge margins. Let’s take an example - Yadkin County, which is circled on the map in green. Yadkin has just 37,000 residents, compared to the nearly 400,000 living in urban Forsyth County just to the east. Republicans tend to win these places by really big margins - 50 - 70%. Add to that the fact that there are a lot of these counties in the state, and it adds up to a large number of votes for Republicans.

Blue rural areas. North Carolina also has some blue rural areas, which differ from the red ones in that they contain large populations of African-Americans. Halifax County, which is circled in purple on the map, has a population of just under 50,000 - and 50% of them are African-American. Because African-Americans tend to vote Democratic by a huge margin - something like 9 to 1 - Democrats tend to win these counties, which mostly lie in the northeast of the state around that purple circle.

Telling a story

That’s a quick primer on North Carolina’s political geography. Now here’s how to make sense of it.

North Carolina is one of the fastest-growing states in the United States in terms of population, with most of that growth occurring in urban areas. Wake County, which contains the state capital of Raleigh, saw a population increase of 25% between 2010 and 2020 - and it’s estimated to have grown by another 5% in the last four years. The people moving to Raleigh and the surrounding region are mostly coming from Atlanta, New York, and the suburbs of Washington, D.C., pushed out by high house prices at home and pulled in by a cool urban culture and good jobs in a relatively affordable location. The places they’re moving from mean that they’re likely to themselves be fairly liberal, adding to the blue-voting population of the state.

This growth is one big reason why North Carolina is becoming increasingly competitive in presidential elections. But there’s another story to be told as well, one that it being repeated all across America. And that story is the relative de-population of rural areas, driven by a lack of economic opportunity and poor public services as the state’s traditional rural industries enter another decade of decline.

Take Yadkin County, our Trump-voting rural county from above. Yadkin was actually the most Trump-voting county in all of North Carolina in 2020. But its population - which is overwhelmingly white - has actually been shrinking, experiencing a 3.1% loss from 2010 to 2020. That’s actually not particularly steep compared to some other places, probably because of its relative proximity to desirable urban locations. The decline in other places between 2010 and 2020 was much steeper - a 9.4% loss in Graham County and a 6.4% in Stokes. In fact, of the 20 counties in which Trump had the largest margins in 2020, more than 50% have been losing population over the last decade.

Not all of the people who leave these rural counties are necessarily leaving the state - many are simply moving elsewhere within it. There are also signs that this decline might be being offset by the impact of remote work and early retirements brought about by the pandemic, but this implies people moving out to the sticks from denser urban cores - and probably bringing their politics with them. But what is definitely not happening is that many new conservative voters are moving into the rural areas of North Carolina to offset the new Democrats moving into the cities. There’s a population flow from Atlanta to Raleigh, not from rural Tennessee to Yadkin County.

Another long-term trend which is affecting North Carolina, along with many other states, is polarization. Put simply, rural areas are becoming more Republican and urban areas are becoming more Democratic. Obama won vote-rich Wake County by 14.45% in 2008, whereas Biden won it by 26.45% in 2020. Ultra-Trumpy Yadkin went to Trump by a whopping 61% in 2020 compared to about 51% for Romney in 2012. It’s an illustration of how the United States is becoming more partisan and divided. And it also has consequences for how you ought to follow the election.

Following the election in North Carolina

Here’s how to watch the election in North Carolina:

Watch turnout. This degree of polarization means that North Carolina is divided into a blue bloc and a red bloc. To win an election, persuasion is less important than base mobilization, meaning turnout is crucial. Obama’s 2008 victory was powered in large part by huge turnout among African-American voters which then waned in subsequent years. Trump won in 2020 thanks to an enormous level of enthusiasm among his own base. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some of that enthusiasm has dissipated, while women, African-Americans, and younger voters are enthused by Harris’ candidacy. If the Trump coalition really is less motivated and Democrats are more excited, as polls seem to suggest, that could put Harris over the top.

Watch the margin in some key counties. As the results start coming in on election night, look at the margins of victory in the key counties mentioned above. Of course Trump is going to win Yadkin County - but it matters by how much. If his margin slips compared to 2020, then he might be in trouble. The relative difference in numbers of voters might be small, but Trump needs to run up big victories in a lot of different rural areas in order to prevail - otherwise, his dreams of the presidency could die from a thousand cuts. The same goes for Harris’ margin in urban and northeastern rural counties.

Watch what the candidates do. A good indication of what the candidates are doing - and what they’re worried about - is where they campaign. Since Harris entered the race, Trump has shown his concern by making two visits to Asheville in an apparent attempt to shore up his support in the rural counties nearby. Harris gave a big policy speech (as opposed to a campaign rally) in deep-blue Raleigh and is yet to visit more rural parts of the state, as she recently did with a bus-tour through southeastern Georgia (where many of the same electoral dynamics apply). It looks like Trump is on the defensive and trying to juice his base, while Harris is getting North Carolina-curious but not yet not taking the state too seriously compared to other must-win battlegrounds. If that changes, it tells you something.

Questions or comments? Suggestions for a future swing state guide? Leave a question below or join the chat. Paid subscribers can start new chat threads.