Trump’s election and chaotic first days in office have been bad news for right-wing leaders in Australia and Canada, who went on to do unexpectedly poorly in elections. The same dynamic - of Trump driving voters away from the populist right - also appears visible in The Netherlands. Is this the harbinger of a broader rejection of the forces of the right in Europe? I asked guest author Martijn Van Ette to explain.

Trump’s electoral victory and his aggressive policies have reshaped European politics. That’s evident here in the Netherlands, where Trump’s efforts to restructure and undermine the global and economic order has summoned a pro-European energy unlike any seen in years. The result has been to drive a wedge between right-wing Dutch populist parties and the electorate. By doing so, Trump is undermining the European branch of the movement which brought him the White House.

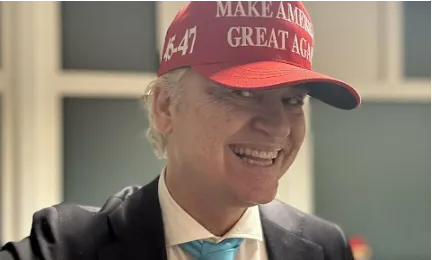

The Netherlands, although small in size and population, is a relatively rich country. But like many other countries in the West, it has suffered from a set of conditions that have enabled the rise of populist parties. Rising costs of living, stagnating wages, a housing crisis, and a series of political crises have eroded public confidence in the government. This created a fertile context for the Netherlands’ most populist politician, Geert Wilders, who is often called the Dutch Trump (he even has similar hair), to prosper. In 2023, his Freedom Party (PVV) dethroned the country’s main center-right party, the VVD, in parliamentary elections, bringing its 13 year long leading role in Dutch coalitions to an end.

Geert Wilders’ party ran on a campaign that will appear familiar to many readers. He combined blatant anti-Islamic rhetoric with supposed solutions to economic and social deemed too-good-to-be-true by expert economists. His party program suggested stopping military support to Ukraine, referred to immigration as a dangerous ‘tsunami’, proposed to fully cut funding to the Dutch equivalent of USAID, and advocated for an end to all climate policies and regulations.

By doing so it heavily echoed MAGA themes: deeply xenophobic, it harbored an implicit longing for a period in history when the nuclear family provided a solid basis for social and economic security. In that sense, it isn’t surprising that the opening statement in the coalition agreement which established the current government is ‘letting the sun shine again in the Netherlands’ – not too different from Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’.

Unsurprisingly, Trump’s victory was welcomed by Geert Wilder’s PVV and right-wing Dutch media. They welcomed Trump’s culture wars against ‘woke’, watched jealously as Musk set up DOGE to dismantle the US bureaucracy, and applauded his crackdown on immigration. Having failed to accomplish most of their own objectives since taking office, the populists admired how Trump pursued his policies with a degree of vigorousness. They wanted to do the same.

But this initial enthusiasm was short-lived. Trump’s inauguration and his administration’s continuous bashing of America’s traditional allies across the Atlantic became a big problem for Wilders’ party. The PVV had seen its polling worsen gradually over 2023, but still was polled to have held on to 35 of the 37 seats it had secured in the parliamentary elections. Three months into Trump’s second term it has fallen to 28, beating Frans Timmermans' social democratic party and the traditional center-right, both pro-European, by just one one seat each.

Even as many Dutch voters have flirted with the populist right, Trump’s behavior called into question the wisdom of a long-term marriage. Calling European states delinquent and free-loaders is one thing – calling them ‘bad’ allies despite their sacrifice of young men and women in support of America’s questionable interventions in the Middle East is another. So is unravelling the trade-oriented world order on which Europe’s prosperity is built.

Both sensitivities resonated negatively within Dutch society and politics: 27 Dutch soldiers lost their lives in Afghanistan and Iraq in a response to invoking Article 5 over 9/11, and 82% of its economy is dependent on exports. MAGA suddenly looked like an adversarial movement opposed to Dutch interests.

This negative view of MAGA worsened after some of Trump’s decisions improved Russia’s position in the Ukraine War. To the Dutch public, this meant that he was siding with the aggressor in a conflict that has caused direct trauma within Dutch society. In July 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight MH-17 was shot down over Ukraine with 196 Dutch citizens on board. Since this flight had departed from Amsterdam, was on its way to a popular holiday destination, and took place during the summer holiday, many of those 196 victims were families.

The trauma did not end there: pro-Russian separatists blocked access to the crash site for days and it took a full week before bodies of the deceased were loaded onto trains to be identified and repatriated. In the meantime, Russian leader Vladimir Putin denied any involvement and sat back while footage and reports circulated in Dutch media about separatists looting the bodies of the victims.

The Dutch government went so far as to prepare an armed intervention in Eastern Ukraine to secure the crash site and repatriate the bodies of the victims. Ten years later, the sight of Trump appeasing Putin in a conflict that had killed 196 Dutch citizens did not reflect well on the PVV, who had until recently applauded Trump’s victory.

Dutch opinion has also been shocked by Trump’s flirtation with withdrawing US forces from the continent and making America’s commitment to Article 5 conditional. This opens a plausible way for a European NATO - Russian conflict to emerge in which the United States could watch neutrally from the sidelines.

The Dutch army currently keeps a force of 700 soldiers in the Baltics, which would be one of the first to see action if that were to happen. In that scenario the Netherlands would not be afforded the luxury it had in 2014 to consider military intervention in Eastern Europe. Rather, it would be forced to. The more Trump undermines NATO, the more likely war is.

As a result of all of this, Trump actions has summoned a wave of European energy not seen since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Support among the Dutch for a European army, ramping up military aid to Ukraine and decreasing Dutch dependency on US big tech surged since Trump’s inauguration and sent voters to vocally pro-European parties. If elections would be held tomorrow, European sceptical parties would receive a mere 20% of the seats according to recent polls, down from almost one third in 2023.

It is becoming increasingly clear what Trump means for Dutch politics – the undermining of the populist right, and the resurgence of the center and left. Whether more influential European countries will follow that example is too soon to call.

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support America Explained and to make it possible for me to recruit more guest authors.

Trump isn't an isolationist. He's something much worse

A lot of Europeans worried Trump would be an isolationist. What if he's something worse - a cultural crusader out to transform Europe into a far-right dystopia?

My fears about the MAGA-Silicon Valley alliance

The MAGA-Silicon Valley alliance, if continued, could have profoundly negative consequences for the future of humanity.

Ok, interesting shifts in the polls. But what is missing here is how Wilders has always been outspokenly pro-Putin and even showed up in the Doema, so his supporters don't seem to mind that connection that much at all, let alone via Trump.

Also, 'housingcrisis' is an overstatement of what is happening there, it is rather following anti-migrant rethoric.